REC articles are not the view or opinion of Alpha Extract Administrators

HOW TERPENES CAN BECOME PLASTICS & ROCKET FUEL

Mediame.guru

Terpenes are a hot topic in the cannabis and hemp industry today for the rich scents they impart to cannabis flowers and extracts, but did you know that terpenes could also be made into plastics — and even rocket fuel?

When people talk about how hemp has “25,000 uses,” one of the uses they frequently extol is hemp’s ability to make plant-based plastics. Since the 2014 Farm Bill allowed hemp cultivation back on U.S. soil, a hemp-based plastic market has picked up steam in the country, though high costs have kept it relatively small. But now, there’s increasing murmurs about the possibility of terpene-based plastics — and even terpene-based rocket fuel.

Terpenes are the aromatic oils that the cannabis plant (and other botanical plants) produce which give it distinctive flavors and smells. They are found primarily on cannabis and hemp flowers, and because federal law distinguishes between cannabis and hemp based upon a 0.3% THC rule, terpenes can be derived from both cannabis and hemp.

As terpenes have disrupted the THC-dominated world of cannabis, they could be even more disruptive to the petrochemical industry. That’s because new research shows that terpenes can be turned into a resin that can make plastics. To better understand the work currently being done with hemp bioplastics and bio-fuels, HEMP reached out to four experts, who let us know why the future of terpene-based hemp plastics might be far off.

The Present: How Hemp-Based Plastics Are Made From Fiber

At the moment, the plant-based plastic industry is gathering momentum as the environmental costs of single-use plastic become more widely known. When it comes to making plant-based plastics, the plant fiber, or cellulose, is used as the feedstock.

Hemp has long fibers that make it useful for making plant-based plastic, but those fibers don’t come from the same parts of the plant (the flowers) that are used to make CBD oil. Hemp is not grown for plastic production in the way it is grown for CBD or hemp oil, the plastic is made from the waste parts of the plant.

“We are using waste hemp that was burned in the field,” Kevin Tubbs, the chief business development officer for The Hemp Plastic Company (HPC), told HEMP. “We are turning a compost pile into a pile of cash.”

The first step in turning garbage into gold is taking the raw hemp stalk and processing it into a form that companies like the HPC can make into pellets, and that first step in Colorado is handled by companies like 9Fiber.

“We turn stalk and stem waste into fiber where we can control the tensile strength and cellulose hurd becomes plastics or semi-conductor materials,” says Adin Alai, CEO of the hemp fiber processing company 9Fiber.

The whole process takes just 90 minutes and their proprietary technique claims to remove all the heavy metals, pesticides, THC, CBD and other contaminants. What 9Fiber is doing is not new and Alai admits “you can get fiber from Germany.” What is new is the price, as the imported fibers are much more expensive. Alai says, “Since our costs are low, we can compete with the materials that industries are already using,” which increases their likeliness to switch over to hemp.

From 9Fiber, those hemp hurds would go on to a company like the HPC, which makes plastic resin pellets. Tubbs echoed Alai, saying the cost of hemp plastic “needs to be competitive” if industries are going to adopt it.

According to Tubbs, a major selling point of their polymer is that they are “a drop-in replacement for the raw resin,” meaning Tubbs can “take someone who has been using nothing but oil-based plastics and convert them over.” For Tubbs, even if companies use a hemp resin blend, “the bottom line is every ounce of hemp we add is an ounce of polymer we did not add.”

The final step in making hemp-based plastics is manufacturers, or molders, melt those pellets down into a myriad of plastic products. One such company is Sana Packaging, which produces affordable hemp and ocean plastic packaging solutions for the cannabis industry. Sana’s co-founder and chief strategy officer James Eichner told HEMP that “the big challenge for circular packaging is finding markets, companies, and municipalities who are on board with an idea like this.”

Eichner stressed the importance of companies using sustainable packaging solutions, because currently, “the negative externalities of what we do are not calculated into the price.”

In other words, there is no carbon tax on products that use more fossil fuels. Even though we don’t see the costs of those packaging decisions in the short term, in the long term, they are contributing to global climate change.

The Future: One Giant Leap for Terp-Kind

Currently, hemp plastics are made from fiber — but what if hemp plastics could be made from hemp-based oil in much the same way that plastics are made from petroleum?

Recent research by the University of Birmingham has demonstrated a technique that can turn terpenes into resins for polymers which “could lead to a new generation of sustainable materials.”

The researchers found that “different terpenes produce different material properties” and their next step will be “to investigate those properties more fully to better control them.” While that research may sound groundbreaking, the scientific community has known polymers can be made from terpenes since 1937, the same year that the Marihuana Tax Act was passed, banning hemp and cannabis in the U.S. for the first time.

Recent research by the University of Birmingham has demonstrated a technique that can turn terpenes into resins for polymers which “could lead to a new generation of sustainable materials.”

As innovative as terpene polymers are, how commercially viable are they? Emily Backus, sustainability advisor for the Denver Department of Public Health & Environment, saw only one scenario that would work, one “where someone is growing hemp for the fiber and the terpenes become a waste product which can be used for polymers.”

While that may not seem a likely scenario now because of how in-demand and expensive terpenes are, as the price of hemp grown for cannabinoids and terpenes drops (as it has for cannabis following state legalization), more people could theoretically begin to grow more hemp for fiber, leaving the flower (and therefore the terpenes) as a byproduct.

Sana’s Eichner also had some concerns, asking: “Can the process reach economies of scale where it can compete with other plastics?” He noted, in more detail in a 2018 piece for HEMP, how even fiber-based hemp plastic still has not even reached an economy of scale. However, Eichner noted that Sana is “material agnostic as a company,” adding: “If someone is making a polymer out of terpenes in a sustainable and commercially viable way we would have no problems using that material.”

What About Terpene-Based Fuel?

Air travel is one of the worst producers of greenhouse gases, and that’s in large part because of the energy it takes to create jet fuel (from the nonrenewable resource of petroleum).

However, research has shown that certain terpenes have been demonstrated to work in fuels that produce enough net heat to be comparable to JP-10 tactical missile fuel, which is also known as rocket fuel and can cost up to $25 a gallon from petroleum sources.

“I think rockets and aviation fuel are the areas where we need some of the most innovation to figure out what we are going to replace with petroleum,” said Backus. She noted that, while we have biofuels mostly figured out for cars, we have no good solutions yet for air travel, so this terpene research looks very promising.

In fact, these terpene-based fuels looked so promising to the Department of Defense that the U.S. Navy has a patent on them and they have been studied by the Department of Energy. Perhaps the next time you fly, the terpenes you smell will be coming from the engine rather than someone trying to discretely hit a vape pen in the next row.

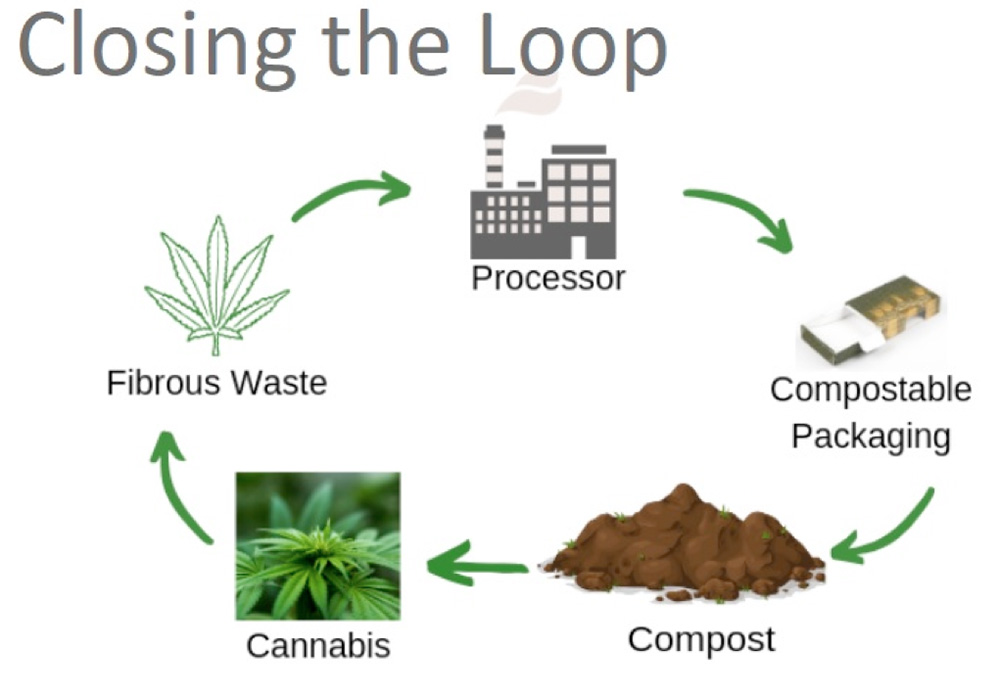

Closing In on a Circular Economy

The ultimate goal of using the waste parts of plants to produce fuel and packaging is to create what is known as a “circular economy,” an economy without waste because resources are reused at the end of their life instead of being sent to the landfill.

Backus gave a presentation on how that could work for the cannabis industry at the recent North American Hazardous Materials Management Association Conference in Denver. When asked how close we are to realizing a circular cannabis economy, Backus didn’t sugar coat things: “I don’t think we are very close but I do think we are at least getting closer to having all the puzzle pieces in place.”

Photo Denver Department of Public Health & Environment

She said it comes down to “a question of infrastructure and technology,” and that price is a factor because sustainable packaging “is more expensive than traditional packaging, so we need consumers to be willing to pay more or brands to be willing to deduct that from their bottom line.”

A major selling point to companies adopting sustainable packaging, said Backus, is that “consumers want to buy from companies that share their values.”

Alai concurred, saying: “Consumers are looking for products, and packaging, that fits their politics and will pay a premium for companies with a sustainable message and sustainable packaging.”